Working in a coal mine

by Doug Brodie

The Telegraph runs a weekly column called the Telegraph Money Makeover – readers write in if they are seeking help with their finances and the journalist of the day contacts firms like ours to ask if we’d like to write in with recommendations in return for getting name-checked in the paper (we’ve been there several times over the last few years).

The case of Richard Brown struck me. Tube drivers earn £62k per year, Richard earns £90,000 per year as a train driver. Irrespective of journalists’ views of earnings, I can tell you that’s a lot compared to the people we see, the careers and businesses they’ve had. A ‘junior’ doctor with eight years post qualification training has a base salary of £58,000.

Read the Telegraph article here

My school was on the west coast of Cumbria, a section of coastline, from Workington to Barrow, famous for three things:

the Windscale nuclear power plant

the heart of the west coast coal mining industry and

frequent winner of the UK’s ugliest train line.

As time pushed us all towards the end of our school time, we had a weekly tutorial from someone working in the local community, invited to talk to us about the reality of the working life, everyone from our local GP to the vicar, the accountant and to the man who owned the local shoe shop and carved the local wooden clogs.

Being an impressionable 17 year old obviously I bought a pair, though not least because the cobbler’s son was a good mate in my year.

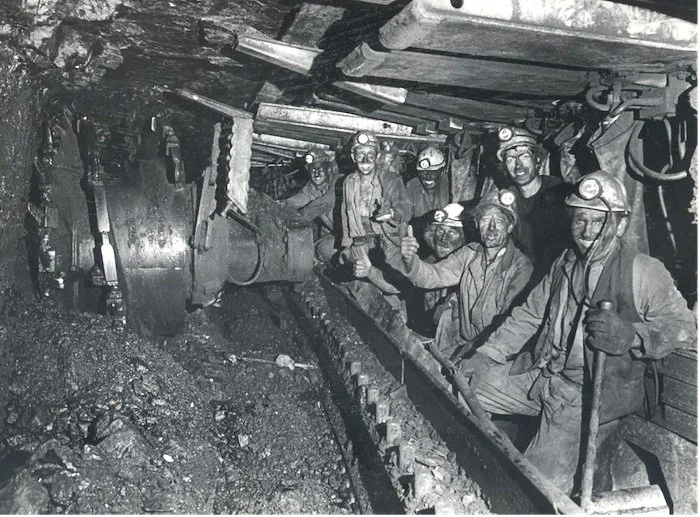

Perhaps the person I learned most from was the man from the Haig Colliery in Whitehaven, four miles up the road from school. Coal mines in west Cumbria mined an enormous seam of coal that extends far underneath the Irish Sea, and it is this seam that has been the centre of the recent political argument with the planned opening of the new Woodhouse Colliery (again in Whitehaven).

The tutorial was in 1977/8, which was six years before the miners’ strikes, however, the issues were clearly building in that part of industrial relations about to destroy the lives of miners. The chap was a shift manager, and the first part of his talk was about his mine, the Haig Colliery, and impassioned he certainly was: shut since the 80’s, Wikipedia provides it with a whole page and this is one excerpt:

An explosion occurred on 13 December 1927 which killed four men. On 9 February 1928, efforts were made to go in and check on the state of the mine, the 800 miners of the interconnected Wellington Mine had gone back to work on 3 January 1928, but the 1,100 miners at Haig were still unable to return to work. The check of the mine was also used as an effort to recover the body of Harold Horrocks who had not been recovered since the 13 December accident. A body of 24 men entered the mine to assess the damage and various trips back to the surface for sustenance and to re-fill breathing apparatus were undertaken throughout the day and night. Sometime after 11:00 pm, three explosions rocked the area, each more violent than the last. 11 survivors managed to navigate the 3 miles (4.8 km) in the dark to the bottom of the shafts where another rescue party was sent down the mine. The canaries that the rescue party carried with them soon died and when the second rescue party reached where the last explosion occurred they found the roof completely collapsed and extensive damage. As there was evidence of another fire, the area was sealed off (and has remained so since) which meant that the 13 people in the initial party and the body of Harold Horrocks were never recovered. As the area was sealed off, a definitive reason for the ignition point for the explosions was never conclusively reached.

Picture: Roberts Environmental

What stuck in my mind was where he went in the discussion after the half-time tea and Wagon Wheels. Bearing in mind we were a room of 17 year olds and this was 1977, he said he knew we all had cars and that the life he was describing was nothing we would ever know as we would finish our time at school and drive down to the continent in our convertibles. “You lot all probably live in mansions I expect”. And the next half hour was spent listening to him outline why – in his view – we were over-privileged, never a money worry, and would never have to spend a day in hard graft.

Our experience from being privileged to have been allowed to share people’s financial secrets and lives is that the outliers are just that, and the majority of those with relevant savings at retirement are in that position because of the teachings of Mr Micawber, not because of excess earnings (the outliers). I wonder if the Money Makeover journalist has a clue about the awkwardness in writing up a train driver earning £90,000 per year when the nation’s train unions are shutting down the railways in a dispute over drivers’ pay?

Being a miner’s a helluva job and I have huge respect for those people still facing deep shafts; we also know the details of young teachers facing the challenges of inner-city local authority schools, and junior doctors on 100-hour weeks juggling the life and death of others for less pay than a train driver.

You might be wondering how a piece of social narrative has wandered in a financial services blog – the point I’m dragging out is that we judge our financial selves with reference to others we see around us, and from our side of the desk, we see that many folks are getting that wrong. The trouble that creates is that people have incorrect expectations and fractured values. We tell our kids that Love Island is not reality and warn them of air-brushing and the reality of what normal bodies are supposed to look like. We are guilty, though, of harbouring our own insecurities of what wealth is supposed to look like and what success should look like.

This is the week of the Dusseldorf Boat Show: it is the largest in the world and has two halls set aside just for super yachts. One of those halls (7a if you’re going) is restricted to yachts over 33m / 108ft long. It’s as hard to imagine the cost of owning and operating one of these as it is to fathom out the logistics of transporting and staging such a boat.

We have various commentaries hitting our media at the moment about the growing difference between the haves and have-nots. We have a terrible fracture within our society when ‘Bank of Dave’ reports single mums taking loans to buy formula milk, whilst at the same time we have the vulgar displays in Dusseldorf. There’s a continuous commentary on the super-rich and how we should consider ‘capping’ personal wealth. Again, from our insights in working with the very wealthy, happiness is not aligned with wealth – it tends to come with financial freedom from bills, allowing you to have time, not ‘things’. We used to have two married clients who worked as crew on board a super yacht owned by one of the world’s richest men (pre-Russian money). The owner was only ever seen on the yacht for one week in any year, and they eventually resigned after he had not been on board for three complete years. As the man said, you can only sleep in one bed at a time.

Whether Elon Musk or Bernard Arnault are worth $150m or $100m is irrelevant – it’s not money in the bank, it’s share values, and if they ever tried to sell, they would simply implode their own wealth. The numbers are a media dog whistle, they are trotted out to amaze people, motivate others and also to wind people up. The Dusseldorf boat show has more to do with personal boredom and inability to think of a useful use of money than it has to do with recreational wishes. As they say, there are two great days for any boat owner.

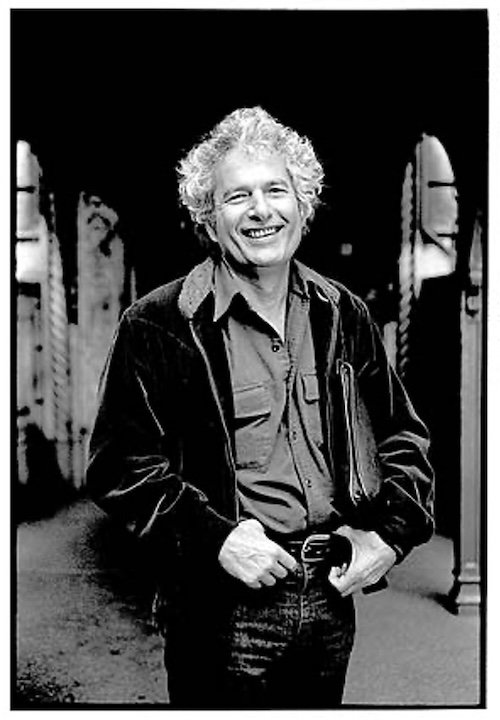

The message we want to impart with this blog is that the wisest commentary on financial happiness is encapsulated by Kurt Vonnegut in his The New Yorker obituary for Joseph Heller in 2005:

True story, Word of Honor: Joseph Heller, an important and funny writer now dead, and I were at a party given by a billionaire on Shelter Island.

I said, “Joe, how does it make you feel to know that our host only yesterday may have made more money than your novel ‘Catch-22’ has earned in its entire history?”

And Joe said, “I’ve got something he can never have.”

And I said, “What on earth could that be, Joe?”

And Joe said, “The knowledge that I’ve got enough.”

Not bad! Rest in peace!”

— Kurt Vonnegut

“Enough”