Tonto

by Doug Brodie

In this blog:

/1. Asset rich, and cash poor

/2. Tontine, not Tonto

/3. Lifetime Allowance - a note from Martin

In 2008, we had the GFC (as the City types call it, Global Financial Crisis), and that threatened to collapse banks around the world in the same way as Lehman Brothers. What happened (and again with Silicon Valley Bank) is that the bank ran out of physical cash to pay its creditors when due. That meant the bank was insolvent and had to close. However, if the bank had more cash and less ‘other-assets-on-its-balance-sheet’ it may well not have been insolvent and could have survived.

Just imagine back to when you were fully mortgaged-up, with a loan that was always subject to a maximum % value of your property. Now imagine if the bank had written to you after a year or so saying that neighbours down the road had sold their house because they had lost their jobs and had no positive future and had to quickly sell the property as they couldn’t afford their mortgage. Next, your lender says that because their house had been sold at a low price (a fire sale), that then was the market valuation for all properties, so your loan-to-value was now too high and you had to repay your mortgage.

In 1992, you will have remembered dining table conversations about people with negative equity, when the mortgage debts were higher than the value of the house. In those cases, the price that someone else sells their home for has little or nothing to do with the price of your home because you are not selling, and absolutely would not be tempted to sell at the fire sale price from down the road.

Value of an asset is the price at which BOTH parties agree to a transaction; it is not the price the buyer touts, and not the price the seller wants to get.

In the banks in the GFC, they had to value all their bond holdings (think gilts, US treasuries, corporate loans) according to mark-to-market. The trouble was that the regulations said that banks had to have x% cash for their solvency margins (see Lehman’s and SVB above), so they started selling their bonds for cash. As Bank A sold to cash, it pushed the price of bonds down because ALL the banks were selling, which meant that the rest of the bonds that Bank A held were now worth less, meaning they had to sell even more, and…and…you can see the vicious circle. The US authorities brought the GFC to an abrupt halt by simply removing the need for market-to-market valuations – in the same way that your house value is actually what would tempt you to sell, so the bonds held by Bank A could be valued at their worth to the bank, not to some forced seller who has come unstuck.

The other area where you and I are acutely aware of solvency and why that is often an incompetent measure of value is the simple difference between holding value in property and not in cash (a bit like the speculators in FTX).

/1. Asset rich, and cash poor

Without liquidity we can’t pay our gas bill, so when we are working with clients on planning, we are acutely aware of liquidity issues and their solutions. There are a couple of things that are plainly obvious in the future of personal wealth and independent income: let’s say it’s 2035, Joe is now 92, lives in the family home worth £2m, and has a pension pot of £2m as well. He can pass on the pension pot to his kids and grandchildren IHT free, however, the house is likely to create an IHT bill of (say) £600,000.

How about Joe ‘spends the house’ and passes on the pension? If he sets up a reverse mortgage on his house to raise cash to live on, he won’t pay income tax on that cash, and will the interest payable to the lender be more than the £600,000 IHT paid to the government?

We believe that people needing income/cash top-ups should first consider this - downsize your equity, not your home.

If you’re not convinced about the subjectivity of valuations, consider that WeWork had a value of $47 billion in 2019, and forty-eight months later it is subjectively valued at $ zero – it’s gone bust. It hasn’t spent $47 billion in that time; it’s just that back then, speculators chose to value its shares, one by one, at a price that totalled $ 47 billion. No one, of course, paid $47 billion in cash, it was just a nominal calculated value.

So it is with your investment trusts – just because someone on the stock market needs to raise cash by selling their shares, that does not mean that the value to you – the income stream – is now less. Like your house, your shares are not for sale at someone else’s fire sale price, they are much more valuable to you. The income reasons that we use income assets are why we now have some ridiculous yields – the income has not risen, it’s stayed the same, and it’s the share price that’s fallen:

Phoenix 11.06%

M&G 9.73%

Legal & General 8.84%

/2. Tontine, not Tonto

(Ok, when was the very first episode shown on TV?)

A tontine is a mutual financial arrangement in which everyone pools their money, agrees to receive a ‘fair’ payout while living, and then forfeits their account on death. A mutual annuity. This is coming back, having originally been around in the 19th century, and then pretty much withered on the vine following several scandals. In 1905, it was estimated that 7.5% of America’s total wealth was held in tontine’s covering 18 million households. To this day, tontines are illegal in the US. The main problem they have is that in the tontines of old, the members had a direct financial interest in deaths of other members. It was like buying a life insurance policy on a complete stranger, hoping he/she will die and you get a payout.

There’s a new type of company pension coming in which has its roots in tontines of old – it’s called a Collective Defined Contribution scheme, CDC for short. The investor’s money is pooled, the cash is run by an investment team, and the scheme actuaries calculate the amount of income each retiree can receive each year – the difference being that income is NOT guaranteed and can fluctuate. We like it, we think this is a good idea.

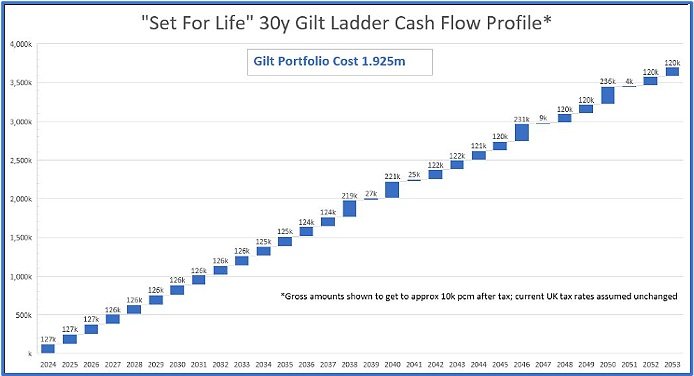

Russ Oxley is launching a campaign for modern tontines and came up with this illuminating chart: this is the finite cost of £10k net per month for 30 years using current gilt prices and yields. The result? £1.925m is the cost of all the income. (Please bear in mind, at the end of 30 years, there’s not left…all gone…so you probably want to allow for some extra, or see my comment on reverse mortgages above).

/3. Lifetime Allowance - a note from Martin

Last weekend Lane Clark and Peacock, a leading pension actuary, published a paper which summarised what has happened to the Lifetime Allowance (LTA) recently and their thoughts on the challenges a future (Labour) government would have if they chose to reintroduce the LTA.

As a reminder, the LTA was abolished by Jeremy Hunt at the last budget. His budget statement was explicitly linked to concerns about NHS retention, in particular senior doctors.

The paper asked a couple of questions and provided possible answers, summarised below.

a) How could the LTA be reintroduced?

By everyone starting with a clean slate – does everyone start again with a full unused LTA? Even if they’ve already taken benefits? It is suggested that this is both unfair and wouldn’t actually raise much money.

By giving everyone a ‘starting score’ – effectively trying to establish the level of LTA an individual had used up previously. Much more difficult with a defined contribution scheme than a defined benefit scheme.

By reference to the available Pension Commencement Lump sum (PCLS), which still has a maximum limit.

b) What about individuals with uncrystallised pension pots which would take them over the LTA?

People may have acted in good faith and in accordance with the new legislation. It could be considered retrospective taxation if individuals were then taxed when they wouldn’t have been.

Would there be a need to introduce ‘protections’, similar to those put in place when the Lifetime Allowance was first introduced in 2006?

Other considerations

Doug is still a member of the HMRC working group, which discusses the issues around the implementation of the removal of the LTA. Rewriting the necessary tax legislation by the target completion date of April 2024 looks increasingly difficult. If a new government is elected in, say, autumn 2024, it is thought they would struggle to get all the required legislation written by April 2025. It may take until April 2026.

What happens then? Does the new government have to write emergency legislation to stop everyone taking their benefits? If this were the case, one could see a scenario where a large proportion of senior doctors would retire immediately and take their retirement benefits, creating a problem of expertise and staffing within the NHS. Also, others with retirement benefits that breach the LTA, would simply rush for the door, taking their benefits early to avoid a tax bill.

Neither of these instances would provide the government the tax income it was hoping for. We think that what is likely is the Politicians Deferral – they would announce the changes, but those taxes would only apply in future years when the current senior staffers (say, aged 50+) have left their professions. A supporting argument to that stance could be that the millennial children will end up inheriting the DC pensions from their parents free of IHT and which they have not paid for.