Looking at money the wrong way round

by Doug Brodie

When King Charles was a prince there was a long-running tale that he never carried money; that was probably correct as he has always had people to do that for him. I suspect, however, that he has probably never read through his bank statements and I’ll doubly bet he doesn’t have a pension app on his phone, nor does he give a hoot about today’s valuation of his investments. (Does he have a pension? Does he use his annual ISA allowance?)

I have no doubt he’ll be briefed by his team on his relevant valuations – periodically – and the decisions to be made will be more like confirmations of the suggestions put to him. The point is that he gets on living his life and performing at the myriad royal functions, leaving the money to perform its own function – be there, pay for things.

People come to work with Chancery Lane because they want income from their accumulated life savings, yet that’s the function, it’s not the real purpose. The outcome sought is to be able to maintain a lifestyle, to be able to afford the expenses of the required retirement. It’s to live the retired life that’s been planned, dreamt of for the past years at work. No one plans to spend retirement counting money or watching the stock market on a daily basis; being an income investor is a job, to do it properly takes time and research when most retired folk would rather be wrapped in families, hobbies, travel, sports etc.

Richard Thaler is a Nobel Prize-winning economist who specialises in your and my relationship with money, what we think about it and how we react with it. It shapes and bends our reactions, if you’re minded to delve deeper, his book ‘Nudge’ is a very straightforward read.

On spending time on investments he writes of Vince & Rip, and I am happy to quote his story here:

Here’s Countin’ Your Money While Sittin’ at the Table

Recall from Chapter 1 that Humans are loss averse. Roughly speaking, they hate losses about twice as much as they like gains. With this in mind, consider the behavior of two investors, Vince and Rip. Vince is a stock broker, and he has constant access to information about the value of all of his investments. By habit, at the end of each day, he runs a little program to calculate how much money he has made or lost that day. Being Human, when Vince loses five thousand dollars in a day he is miserable— about as miserable as he is happy at the end of a day when he gains ten thousand dollars. How does Vince feel about investing in stocks? Very nervous! On a daily basis, stocks go down almost as often as they go up, so if you are feeling the pain of losses much more acutely than the pleasure of gains, you will hate investing in stocks.

Now compare Vince with his friend and client Rip, a scion of the old Van Winkle family. In a visit to his doctor Rip is told that he is about to follow the long-standing family tradition and will soon go to sleep for twenty years. The doctor tells him to make sure he has a comfortable bed, and suggests that Rip call his broker to make sure his asset allocation is where it should be. How will Rip feel about investing in stocks? Quite calm! Over a twenty-year period, stocks are almost certain to go up. (There is no twenty-year period in history in which stocks have declined in real value, or have been outperformed by bonds.) So Rip calls Vince, tells him to put all his money in stocks, and sleeps like a baby.

The lesson from the story of Vince and Rip is that attitudes toward risk depend on the frequency with which investors monitor their portfolios. As Kenny Rogers advises in his famous song “The Gambler”: “You never count your money when you’re sittin’ at the table, /There’ll be time enough for countin’ when the dealin’s done.” Many investors do not heed this good advice and invest too little of their money in stocks. We believe this qualifies as a mistake, because if the investors are shown the evidence on the risks of stocks and bonds over a long period of time, such as twenty years (the relevant horizon for many investors), they choose to invest nearly all of their money in stocks.

From our side of the desk, we don’t disagree with Terry Smith of Fundsmith fame who says his strategy is to buy good companies and then do nothing. Warren Buffett says we should only buy a company that is so good we’ll be happy to hold it for ten years.

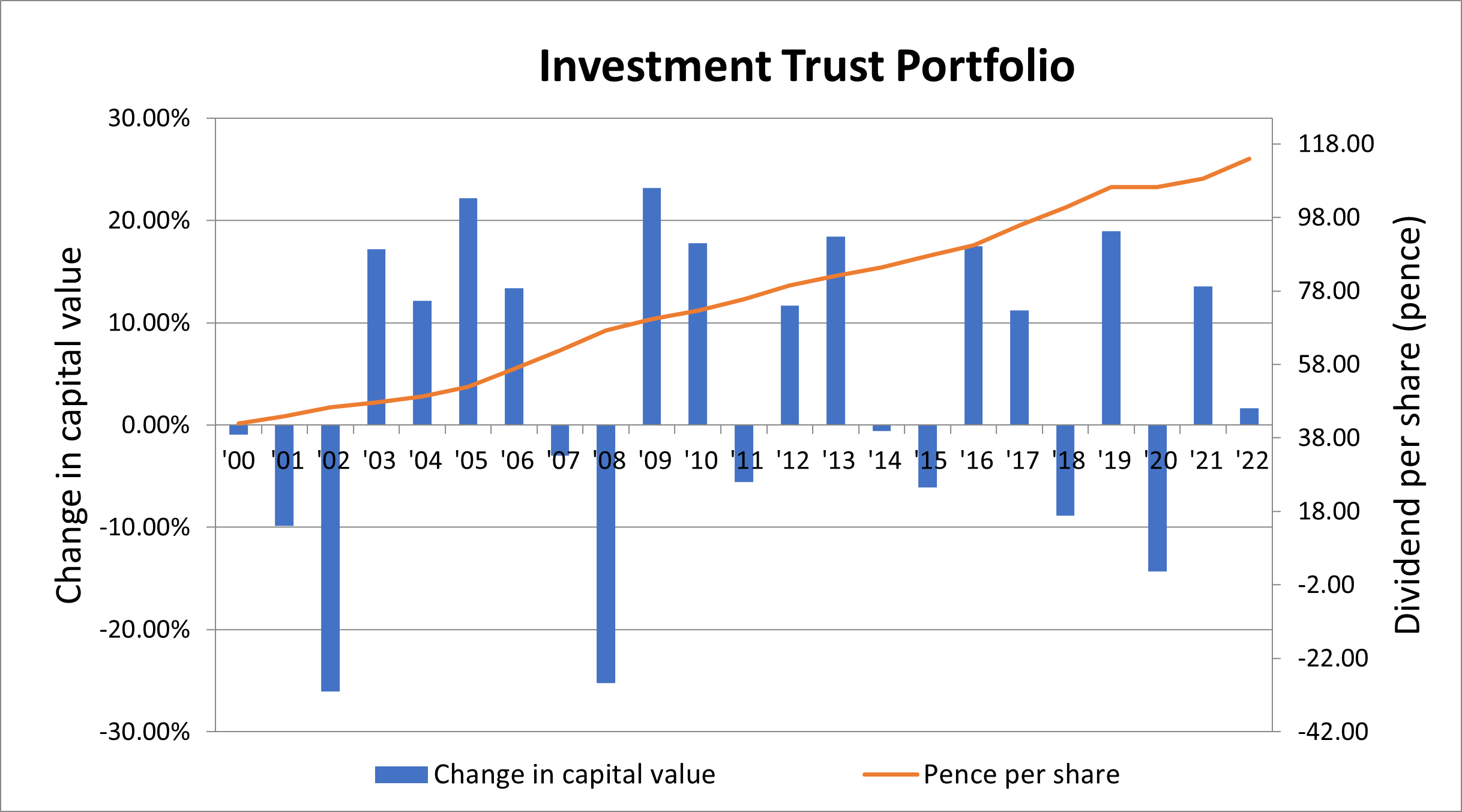

Neither of these gentlemen act on shortterm valuations, they both form long term views of where their investments are going and then don’t touch. The chart below is known in our company as The Key Chart – this version here is bang up to date, covering the last twenty three calendar years. These investments are not guaranteed, however the realistic balance to the word ‘guaranteed’ is that these figures do cover the dotcom, credit and covid crashes within that time, and still the income (red line) confirms its lack of correlation to the share prices (blue bars). Something is working very well, and that item is not smoke and mirrors, it is accrued accounting reserves.

We have yet to publish our update white paper, however Kseniia has now finished the figures; inflation is one of the current watch words for income investors, so within the research we look at how the F&C trust dividend compares to RPI. In the chart below, starting from 1972 (50 years), we plot a single dividend being increased by RPI against the same dividend from one share growing by the rate it naturally increased – and then like Messrs Smith and Buffet, we do nothing and don’t touch.

The moral of the outline above is that money is a facilitator, it’s not about your income its about your lifestyle, and it’s most certainly not about spending your time trying to guess the next twelve months’ asset allocation.

Doug