Inflation – the BBC tells us what it was, JP Morgan tells us what it might be

by Doug Brodie

Calamity Jane’s big song in the movie was ‘The Black Hills of Dakota’ – you probably haven’t heard of Black Hills Corp so we’ll show you why it appeared on our radar.

1942: Singapore was captured by the Japanese, soap was rationed in Britain, Carole King was born and Black Hills Corporation was founded in Rapid City, South Dakota.

Since its founding, Black Hills has paid a dividend to its shareholders every year, for 81 consecutive years. This endows Black Hills with a place in the US’s Dividend Kings, though the longest run of increases belongs to American States Water at 67 years.

Looking across the pond at dividends we see that Colgate Palmolive leads the way with 128 consecutive years of dividend payments, every year since 1894. Other US firms with 50+ years of increases include companies you won’t have heard of like Stanley B&D and Gorman-Rupp, but you will have heard of Coca-Cola, PepsiCo and Johnson & Johnson.

As income hunters, we need to know where we can find the best sources of income, and also ensure that we don’t become too blinkered in our research, being based in London. Also, we look for evidence that dividend strategies are recognised elsewhere (though that could be us falling for confirmation bias).

Fortunately, our trust market provides enough spread of choice to be able to include income from overseas listed firms as well as those on our home turf. If we look at three trusts together to compare the outcome we can see that it’s possible (and relevant) to build your portfolio income with geographical protection.

This shows the income from £100k in each trust over the last ten years; NOTE, income charts are the only time when you don’t have to be worried about a straight line from bottom left to top right. City of London is 88% in the UK, Temple Bar is 98% UK and Murray International is just 3.8%:

City and Temple Bar are both UK-centric. However in their ‘Top 10’s’ there are eighteen different holdings, which is why we frequently run them both together – they are complementary. And to answer all the nay-sayer commentators who avoid trusts because of their ability to gear, City is geared at +7% whilst Temple Bar is cash positive. If you’re a follower of trusts, as we are, you might think Temple Bar’s position could well be dictated by the board as the previous manager was heavily geared at the beginning of 2020 when ‘it all went wrong’.

While we’re looking at these two trusts, these charts below give you a better insight to how we see them, and why looking under the bonnet is important. Like inflation, we want to be comfortable about what the future is likely to be, not what the past was.

The obvious thing to look for is the dividend history, because that is what we are trying to ‘buy’, so here is the annual payment history for City and Temple Bar for the last ten years;

Everything looks hunky dory with City, and you’d be forgiven for thinking this a no-brainer, however it’s important to look at the source of that income if you’re trying to buy income for a stable pension in your retirement; that requires looking at the revenue reserves because THAT is where the dividends are actually paid from. This is the revenue reserves over that same ten years:

The cracks show up in the reserves, whereas they didn’t in the dividends. Now we use City quite extensively because there are many other relevant criteria in assessing a trust, plus we use no investments in isolation, each portfolio recipe has many ingredients: City and Proctor & Gamble are two common ingredients, but from now we’ll also be keeping an eye out for those Black Hills of Dakota (and trying to avoid humming out loud when we find it).

JP Morgan has $2.76 trillion dollars under management, so what do they say on inflation?

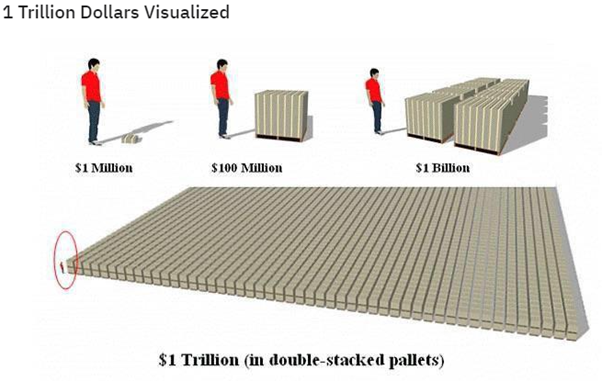

This is $1 trillion, and JP Morgan caretakes 2.76 of them:

This number has more zeros than one can accurately replicate with confidence, but what it does show, is that millions of people and institutions across the globe trust JPM to manage their assets. This week JPM we joined their monthly market update - JPM chief strategist Karen Ward alongside Stephen King, who is the ex-chief economist of HSBC and has recently written a book entitled ‘We need to talk about Inflation’.

Inflation is both unfair and unwavering in the way in which it affects different facets of our economy. In his book Stephen writes that ‘Inflation is preferable to a series of grim fiscal alternatives’ which serves to highlight the delicate balancing act that faces the government. On the one hand there is the huge effect that inflation has upon pensioners due to its erosive nature. On the other are the ‘grim fiscal alternatives’ in which a rising debt to GDP ratio leads to a need for a raid by taxes and greater fiscal tightening* in order to slow the ever-increasing ratio (* politician’s term for spending less).

The government are then left with an unenviable predicament between upsetting the electoral might of pensioners or controlling inflation through means of greater taxation. In this complex situation we must also consider that inflation is a redistributive device as it distributes money to debtors at the expense of creditors. By nature of what they do governments are debtors and an environment where interest rates are below inflation is beneficial for their financial calculations. As a result of this the government may perhaps be more laissez-faire in their approach to tackle inflation than they would be in alternative economic circumstances.

So, what’s the market consensus on inflation and what are interest rate futures markets pricing in?

Both Stephen and Karen agreed that across the market, the general view is that inflation has reached its peak and over the coming quarters it is likely to fall a few percent. In the medium-term inflation is likely to settle back to around 2-3% by around ‘25/26. While there is widespread consensus on the path of inflation there is greater disagreement on the process of getting there and Stephen warned that any attempt to cut short-date rates too quickly would increase the likelihood of a hard landing.

As for interest rates, interest rate futures’ prices move inversely to interest rates and give us a figure over different durations for what the market has ‘priced in’. We can glean these by looking at where different dated interest rate futures are currently trading on the open market, and I have combined these market rates into the table below;

Throughout his book Stephen refers to previous periods of high inflation and tries to highlight any lessons that we as investors can glean. In it, he writes ‘Cash and bank deposits will deliver negative real returns and therefore exercising excessive caution will be penalised’. He does also note that while real assets outperform nominal assets, this period has shown to be a tough time for investors regardless, with much larger than usual periods of volatility that are often intimidating.

When we analyse previous data, we see that during periods of high inflation the gap between professionally and personally managed portfolio returns widens further. This again goes to highlight the natural inequality prevalent in inflation but also highlights the need for a professionally managed portfolio to whether any inflation storm. It’s not easy investing through inflation, more so on one’s own, which is why we think the views of the Big Boys matter, not least because the amount of money they manage gives then the ability to move markets.

Nick Woodhead, client manager.