Jack Bogle’s Rules

by Doug Brodie

/1. Jack Bogle’s Rules

Jack Bogle pretty much started the whole index investing industry. He did it in America for American reasons, and few folks appear to remember that he also started his son’s hedge fund business, so, like Mr Buffett, it’s fair to say his core message to the retail investor is to use an index tracker if you don’t know what you’re doing. Obviously Mr Buffett made himself a wealth of $150 billion by not using trackers but by being an active investor (an awkward truth often ignored by many).

Jack Bogle: pioneer of common sense.

Here are Jack’s top rules for others:

Remember 'reversion to the mean' ...

Time is your friend and impulse is your enemy. ...

Buy right and hold tight. ...

Have realistic expectations. ...

Forget the needle, buy the haystack. ...

Minimise the croupier's take. ...

There's no escaping risk. ...

Beware of fighting the last war.

Reading the list, it starts with his mantra that values average out, performance necessarily reverts to the long term average / mean. You can look this up on the interweb if you wish, there’s some good rabbit holes you can disappear down in learning why arithmetic demonstrates that rule is true.

Time is pretty much the most important factor with retail investors: in the UK, we generally hold most investments in funds, and normal retail funds don’t go bust. In the US it’s a different market, and many investors hold individual stock portfolios. It would be unusual to have a reader of this blog who did not hold pensions/investments through 2020, 2008, and probably 2000 to 2003 – from this you know that markets are cyclical, they fall and then they recover. It’s what they do. So the only retail investors who lost money in, say, 2008 are those who got either their timing or their judgement wrong. If they needed cash in December 2008 they got their timing wrong. If they sold out in March 2020, they made a wrong judgement call.

Overall, the most important of Jack’s rules is #4:

“Have realistic expectations…”

We are about to add to our fact finding a question that asks about specific expectations – in number terms, what do you think investments will return to you? In income or total return?

/2. What a final salary portfolio looks like – would you know what you’re looking at?

You have a pension statement, it shows a simple lump sum value of a pot of money – you understand that, you’ve seen money in the bank before, you’ve seen the value of your pension pot, ISA, investments over the years. Now, however, it’s getting a bit more complicated because you need to swap your pension pot for a pension, and they are not the same thing.

As a reader of this blog, you are entitled to a UK state pension (unless you’re a reader from overseas, of course), and you probably know that that pension is around £11,500 per year. Mr Google tells us that an index-linked gilt – one that guarantees to match inflation – pays a current yield of circa 1.2%. That means that the pension pot required to guarantee that state pension to you is £958,333. That’s quite a lot of money.

The government doesn’t have that capital in an account with your name on it, it doesn’t need to. It knows that some of us will die before we reach pension age, some will last a few years, some many more. Also – and here’s the bit that feeds into the section below this – it chooses to self-insure, meaning it just picks up the cost of your and my pensions from its current account, year by year.

The capital in your pension pot you’ll recognise; however, you probably won’t recognise the make up, the ingredients of an actual monthly-paying pension, one that delivers a regular £X,000 per month to you, and if you don’t recognise its ingredients, how do you know if they are correct?

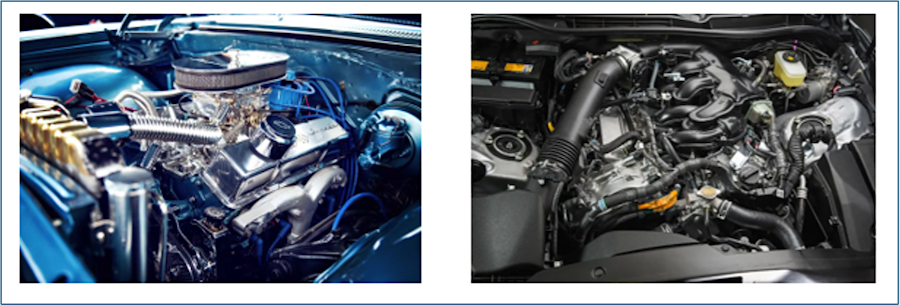

Like the items below, does it matter if you don’t recognise the inner workings of a multi-decade, inflation-matching income stream?

One of these mass-produced car engines is recognised as one of the most long-lasting ever, regularly exceeding 300,000 miles:

Can you tell which is the best and which is the worst? * (Answer at end of blog)

Can you tell the difference between the asset allocation of a final salary scheme and of an investment trust portfolio? * (Answer at end of blog)

Can you tell which one of these you can eat and which one you most probably should not? * (Answer at end of blog)

Molecular formula: C21H22N2O2 Molecular weight: 334,40 C 75,42% H 6,63% N 8,38% O 9,57% Structural formula: 3.3 Physical properties 3.3. 1 Colour Translucent or white 3.3. 2 State/form Crystals or crystalline powder 3.3.

Chemical composition and molecular structure. [(2S)-2-[[4-[(2-amino-4-oxo-1H-pteridine-6-yl) methylamino] benzoyl]amino] pentanedioic acid] is an odorless orange-yellow in color, with a molecular weight of about 441.404 g/mol. It has a melting point of 482°F and its molecular formula is C19H19N7O6.

No? Me neither.

/3. Your self-insured Defined Projected Benefit pension

You are self-insuring your income, except for the state pension you have and any final salary scheme. If you have a pet, like Mr. Mutley here, you can choose to pay £60pm to PetPlan (other pet insurers are available), or – as we like to say – risk it yourself.

If Mr. Mutley has a fine and healthy life, then you will save yourself around £10,000 – that’s £720 insurance premiums x 14 years. When you look at it that way, that’s quite a lot of money to save. But if you decided you’d pick up the vet’s bills yourself, how would you feel about a bill of £8,000 for surgery for this loveable imp? You’d still be £2k quids in over his lifetime, but the cost in the moment would make you feel very uncomfortable. (Unless you’re an actuary, obvs).

We do pensions and income investments – we recognise the differences between final salary pensions and investment trusts, and, in fact, the similarities. The core difference you can’t see is that the DB pensions are underwritten by the employer – if the investment comes up short, the employer gets the cheque book out; with a private investor portfolio, it’s you who underwrites the scheme.

Essentially, the two portfolios are the same, with just the core difference being that the ex-employer is on the lam for the DB scheme. This only kicks in when you’ve retired and you are no longer an employee, however, the employer remains on the hook for the rest of your life. Due to this contractual liability, the schemes play ultra safe, the employer does not want to be adding money to pensions of people who retired from them 5, 10, 20 years or so after they left service; being conservative they hold bonds which themselves are contractual obligations from the companies / governments that borrowed the money.

We use investment trusts because they hold reserves on their balance sheets to smooth the income every year – although not guaranteed by anyone, they are bomb proof. If you buy shares in Law Debenture today, your first year’s dividend is already in their accounts, so practically no risk or reason why that will not be paid. If you build a portfolio of income-focused trusts, you find there’s a £multimillion store of revenue assets already accrued, already available to pay your dividends.

Here are the reserves of one trust we use; you can see the total dividend payment was £41.3 million, and at the start of the year, it already had £33.4 million of that tucked away. This is how we ‘self-insure’ the pensions – like having £8,000 in savings to pay for Mr. Mutley’s surgery, the trusts have £x millions to pay the pension income to you / us every month.

We saw in the section above that it would cost £958,333 to have the amount of your state pension guaranteed (GUARANTEED is the relevant word here), however if you swapped ‘guaranteed’ for ‘probable’, and self-insured the risk, then using Murray Income on its own to produce that income would cut the capital cost to you to just £254,998.

For a saving of 74% of the cost, is self-insuring your pension income a viable option? Probably.

/4. You have £700k in pension and savings, what’s a reasonable NET income expectation?

Don’t forget, if you want that income inflation-linked and guaranteed, the income will fall from £29,400 to £8,400. At which stage, you’re much better off putting the money under your mattress because at £8,400 per year it will last you 83 years before it runs out (nice problem to have).

* Answers:

In the blue corner - Toyota’s 22R engine is often hailed as one of the most robust and long-lasting engines ever produced. Introduced in the late 1970s, it powered various Toyota models for decades. Owners have reported these engines regularly exceeding 300,000 miles, and some even reaching half a million miles with proper maintenance.

And Lexus may have offered a plethora of modern technologies, but the lacklustre motor from the previous generation IS 250 was anything but athletic. Power came from a pipsqueak of a 2.5-liter V6. It was both undersized and overly constricted by power-robbing emissions systems. It left both critics and drivers underwhelmed.

The purple table is the summary of the Purple Book which aggregates data from defined benefits pensions; the red-lined table is the asset allocation summary of a portfolio of 8 investment trusts.

C21H22N2O2 is strychnine, C19H19N7O6 is folic acid.