The Leg Lab

by Doug Brodie

In this blog:

BigDog

Avoid the panic

/1 BigDog

In 1992 Marc and Robert spun out a company from the MIT ‘leg lab’ that worked on developing robotics. In 2004 they demonstrated BigDog, which you’ll probably have seen. With the seed development already done at MIT it took the team twelve years to get to here – I don’t who was funding this, who the backers were/are, and surely in robotics there can be no certainty.

The video link is here - you need to watch it to get a good handle on the actual ingredients of the tube/train strikes when driverless trains have been around since ’63. Look how far we’ve come, and we have to wonder why industrial relations has lagged so far behind.

Such developments are backed by investors using long term capital where the annual return is not relevant, and the quarterly valuation figures compared to the FTSE or any index are simply not relevant. We do think the world will hopefully develop quicker with more venture funding, and if Boston Dynamics can do this for robotics, could CGIAR do the same for food production in under-developed countries?

This is an excerpt from a blog I follow; the wisdom needs no explanation. It does hammer home for all of us that it is compulsory to think of future years and plan ahead. This isn’t luck, this is foresight.

This might be the most important element of investing that a drawdown retiree needs to know – perhaps. It is definitely the most important attribute to understand if you don’t want to make the glaring error of emotional reactions to markets. I couldn’t express it any better than Simon does:

Our industry has become dangerously obsessed with volatility. What was once just a small part of good risk management has become all-consuming: Volatility data increasingly dictates investment decisions and is hardwired into products and legislation. In many cases, this is leading to the exact opposite of the intended outcome: clients are losing money.

Yes, this is another rant about how volatility doesn’t equal risk.

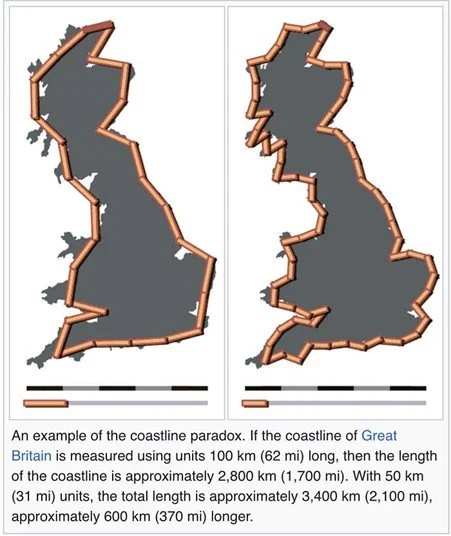

First, however, a tip for your next pub quiz. Not so much for winning it as for finding new ways to annoy the quizmaster (I’m routinely barred from pub quizzes across Sussex). Here it is: There is no official length of Britain’s coastline. Or any other country’s coastline. So any question on that subject can be contested.

You’re welcome.

This is because of the coastline paradox: the total length of any coastline varies wildly depending on the size of the unit used to measure it. If you measure point to point using 100km intervals, Britain’s coastline is 2,400km. Use a 50km interval, it’s 3,400km. And use an inch between your points? It would be multiples longer again. So you can’t give an ‘approximate’ answer and claim it’s anything like accurate, because wigglyness matters.

Measuring the volatility of an asset or a market suffers the same problem: just one reason why relying blindly on a scientifically precise-looking number can be misleading. Do you know which time interval they used? One month? One day? One minute? Or one decade? It matters.

For example, if you were offered the following three financial journeys which would you pick?

Obviously you’d pick option C every time. Why would you opt for a financial rollercoaster when a smoother option is available? But the three are, of course, the same thing: The global stock market in 2020. All that’s different is how often you checked its progress: ‘A’ was checking it every day; ‘B’ was every month; and ‘C’ was once a year.

2/ Avoid the panic

Private Equity

Another problem arises when volatility has been artificially suppressed. By that, I mean that flat-looking past volatility data doesn’t always reflect a genuinely low-risk, stable asset. Sometimes it’s due to a lack of liquidity or accurate, real-time prices.

Private equity is a good example. A private company isn’t less risky than its exchange-listed equivalent. But I’ve heard plenty of investors tout private equity as a risk-diversifying ‘alternative’ to listed equities. It isn’t.

Same for commercial property. A line chart of Bluewater Shopping Centre’s valuation would look flatter than, say, the share price of Vodafone. Is it less risky? I doubt it. The flatness is purely because a property’s value is manually calculated on an infrequent basis, while Vodafone’s is updated by the market every nanosecond.

If you were able to trade shares in Bluewater on an open exchange, the price would rise and fall on a minute-by-minute basis too. (Perhaps that’s not a bad idea for big commercial properties.)

So, Vodafone’s higher volatility simply represents a more accurate, timely and honest reflection of its perceived risks and rewards, whereas Bluewater’s smooth line is an artificial construct. But encouraging investment products based on past volatility data favours the artificial and penalises the truthful.

The result? At times of stress, investors get trapped in artificially inflated assets while their prices are adjusted downwards to match reality. Painful — particularly if you need the money in a hurry.

With the tide going out, we saw many of these risks realised last year. Volatility-managed asset allocations looked ugly, with many ranges inverting: Too many ‘cautious’ products fell further than their supposedly higher-risk counterparts, leaving advisers with the prospect of uncomfortable client conversations.

I’m interested to see the response. With higher volatility now in bonds’ past data, will volatility-focused products be forced to sell assets like gilts? Just as, for the first time in years, their yields reach levels that make them a reasonable prospect again.

In short, there is no easy, industrialised way to manage risk. Data can be useful, but it’s no replacement for a broad, human-based assessment of the real-world risks and rewards of an asset.

But industrialising investment processes is cheap, and the industry’s other manic obsession is cutting costs to the bone. I doubt this trend will reverse, despite the obvious shortcomings that were — again — exposed last year.