Glengarry Glen Ross

by Doug Brodie

In this blog:

/1. Inflation versus dividends: the relevant data

/2. The Rolls Royce Pension Scheme, or, ‘Why doesn’t everyone do this?’

/3. Fees, charges, costs and commissions

/4. Commission or fee – what’s the difference?

/5. Handouts to the kids

/6. Help – she’ll just spend it

/1. Inflation versus dividends: the relevant data.

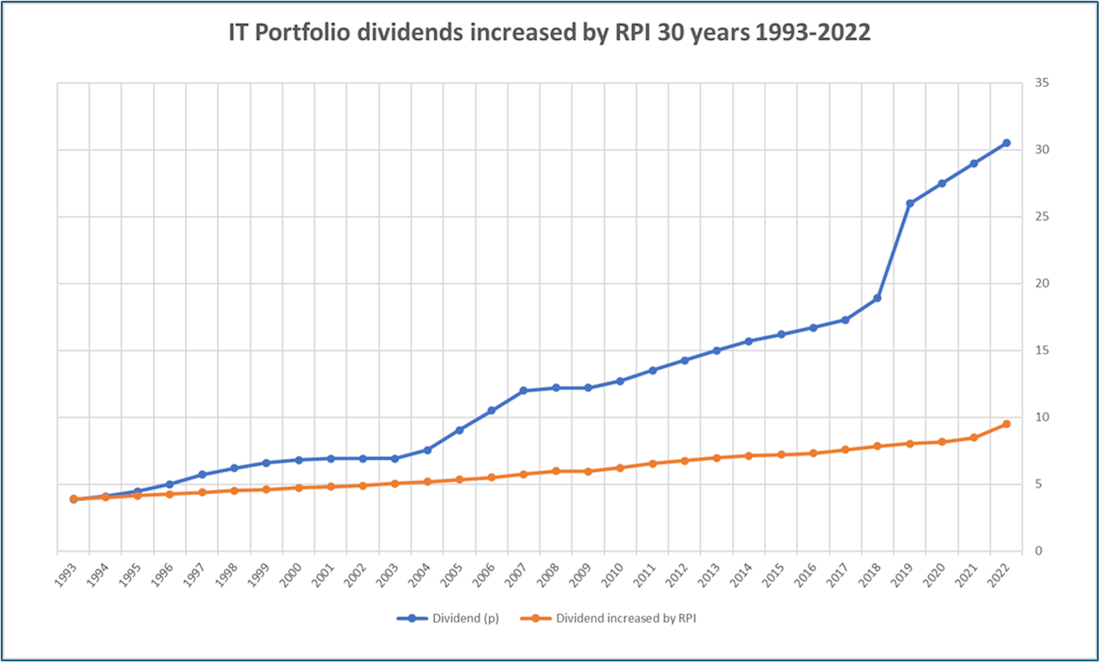

The chart below compares the annual growth of income payments from our core basket of 31 trusts and compares that to RPI. We did this by taking the income from an equal weighting of the trusts in 1993 and then plotting that income to 2022 when RPI hit 11%. That is the blue line. We then plotted that 1993 dividend and grew it each year by RPI – thus showing us what an income tied to RPI would have done. The figures plotted are on a discrete basis, not cumulative.

If you’re over 50 you’ll have found it impossible to do any Google searching on the internet without being bombarded by digital adverts from Fisher Investments from America, their headquarters is in Texas. They manage $197 billion in pooled funds from there, operating as a discretionary fund manager – in essence that means you fill in a risk assessment questionnaire, you get allocated a risk grading and you then get put into the large pot of investment funds that matches your risk grading. They are an American firm, they don’t ‘do’ UK listed investment trusts.

Fisher is an institutional investor, and that means the way they run money is in bulk, based on longevity of the funds. The result of that is this is what a personal portfolio looked like for one of our clients:

The client came to us for two reasons: chiefly it was because he couldn’t fathom how they would make his money make money – he wanted a clear understanding of where the income to fund his retirement would come from. However, he also expected to see that if his money was being pooled with $ billions elsewhere then he should have an economy of scale, whereas his actual fees ranged from 1% to 1.5%.

I have no doubt this is a very competent portfolio, however, it is not designed to produce a constant stream of income, which to us is what a pension should be. More – and most investors probably won’t notice this – in the small print at the top of the valuation you can see their note: “To maximise our likelihood of beating the benchmark…”. We don’t think a client’s pension income should be a benchmark, we think it should be a specified annual income sum that is specific to that client, with a clear source of that cashflow payment from the underlying portfolio. Beating a benchmark is a ‘get out of jail free’ card for an investment manager where success can be claimed even when the client loses money. We think pension income should be absolute.

/2. The Rolls Royce Pension Scheme, or, ‘Why doesn’t everyone do this?’

Not the cars, that Rolls Royce belongs to BMW. This is the engineering conglomerate whose defined benefit pension scheme has 23,000 members and 14,400 pensioners drawing benefits, in other words, a prime example of a large final salary scheme. It has eight investment managers and we have client money run by five of those firms: M&G, L&G, Insight, Hg and Royal London.

The Truss / Kwarteng budget caused a near cardiac arrest for final salary schemes because of the impact it had on the UK bond market (it tanked), throwing into disarray the financial assumptions underpinning the maths behind such schemes. The RR scheme assets fell from £8 billion to £5 billion. Disaster you’d say? Well not quite – the capital value of the scheme’s fixed interest assets (and derivatives) fell, whereas the fixed income from those assets continued. You can see in the table below that the income increased by 22% at the same time as the capital fell by 33%.

More, you can see in this table that the income payments to pensioners were £112m, and this was covered by investment income of £240m so the scheme managers would not have to sell any of their assets to raise cash to pay pension income.

So if the question from a retiring investor is ‘Why doesn’t everyone do this?’, the answer is clearly that the professional funds do, we’re just copying them.

/3. Fees, charges, costs and commissions.

This note is prompted by two recent conversations we’ve had, one with a retired national bank senior bod, and the other with an industry counter-party.

Firstly – there is no commission in retail pensions or investments. Commissions were outlawed by the FCA’s Retail Distribution Review in 2012 – none, no commissions at all. (Though commission is still used in life insurance, as well as your car/house/travel/health insurances).

/4. Commission or fee – what’s the difference?

A commission is a sum of money embedded within a product that is paid to a seller, the amount of commission is determined and controlled by the product provider. It was/is the fuel of salesmen, so excruciatingly displayed in the 1992 film Glengarry Glen Ross.

A fee is a sum that is charged by a professional service firm (planners, solicitors, accountants, surveyors). It is identified at the start of the services contract and paid by the client, either directly or as a specified deduction within a product. The fee is determined by the professional services firm.

I had a recent conversation with a person who had retired from a range of senior positions within retail banks (everything about the seniority of the roles held was demonstrated by the size of final salary pension being received). In the preliminary conversations reference was made to the old days of 5% initial and 1% annual – those figures refer to pre-configured product charges, not advisory fees. The person was aware of them as part of their role at the bank had been negotiating ‘distribution agreements’ with product providers. Times have changed, however, from interest I took a quick look at embedded charges of retail unit trusts still today:

There’s a clear explanation here as to why Terry Smith moved his business to Mauritius (we note his fellow Brexiteer James Dyson also chose to move his business from the UK). You can also see where the money is in the investment sector, there’s clearly not much scaling of charges here. We very rarely see any initial charges on any fund – these are your reference points for who is charging above market rates, and it’s not hard to follow why SJP is in the FTSE100 and Ken Fisher is a billionaire.

As a quick comparison, here are some of the trusts we use:

All fund data sourced from FE Analytics

There can be no initial charge on an investment trust because you can only invest by buying second-hand shares in the market (excluding C share issues).

Chancery Lane is fee only – we charge a fee of up to 0.75% of the value of money transferred to us which pays for the planning work with the client – every client bar none comes in via our cashflow planning work – the investigation and comparison work on an open market basis (it’s a legal requirement for being independent), and the administration and implementation of the plans and portfolios over the first year.

Our annual fee is 1%, charged to the pension/ISA/investment, charged at a rate of 0.0833% per month. This covers the cost of our work and direct expenses, including our in-house research. The value is measured against the objective – delivering stress-free income through retirement, and although not guaranteed, we have never had any client in any year with income lower than the prior year. We work on the same side of the desk as our clients – we are retained to advise and work with you, we do not have a suite of funds to sell like Fundsmith or SJP or Fisher. We currently caretake client money sitting on 11 different platforms with 47 different fund managers – from Abrdn to Vanguard to iShares to Janus Henderson to Fundsmith to pretty much every major investment manager in the UK. We also hold direct shares in dividend stalwarts like L&G, M&G, Lloyds Bank, Phoenix etc.

We have no income other than the fees paid to us by our clients.

It is your money, we are agnostic, we simply crunch numbers and follow the data.

/5. Handouts to the kids.

Being honest, we know that when we were buying our first properties we could use 95% mortgages and 3x salary normally got us there. Not so today, so the kids normally seek a bit of a leg up with deposits, not just because the ‘normal’ loan to value for a first time is now 82%.

Giving to our kids (or nephews, nieces, grandkids) is probably best thought of as a question of timing. As Clint Eastwood didn’t say, ‘No one gets out of here alive’, and if Steve Jobs, John D Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie have shown us anything it’s that wealth does not keep the Reaper at bay. The kids will get the money eventually (we hope), so affordable support is no bad thing.

/6. Help – she’ll just spend it.

Sometimes it’s out of your control, and that’s just the way it is. We had frantic emails last week from a longstanding client with a daughter who has just turned 16, just at the same time as, hmmm, ‘exploring her boundaries’. The junior ISA that the parents had dutifully funded through her life was now a tidy sum and she was quite aware of it. At 16 the kids ‘get control’ of the account but cannot make withdrawals till they are 18. At that stage it’s all theirs, nothing you can do (but it will probably be alright, they are the output of your careful upbringing).

We’ve seen the teenage offspring of clients blow legacies from well meaning grandparents, however, we’ve also seen a divorcee sell the family house and give all the money to her local church (a significant seven-figure sum). By the time our kids get to inherit from us we hope they themselves will be in their 60s, even 70s, at which time their lives will have run through the financial ups and downs. The value of your wealth is best applied to your kids when they need it, when it will make a material difference to their lives. They are the generation who are responsible for our end of life care so we better hope they like the way we treat them!